Text content

The Introduction from the book

Can you imagine how you would feel if you or someone you loved, were told, within a year you will become completely paralysed, become dependent on a machine to help you breathe, lose your ability to speak and swallow, and maybe lose your mental capacity too?

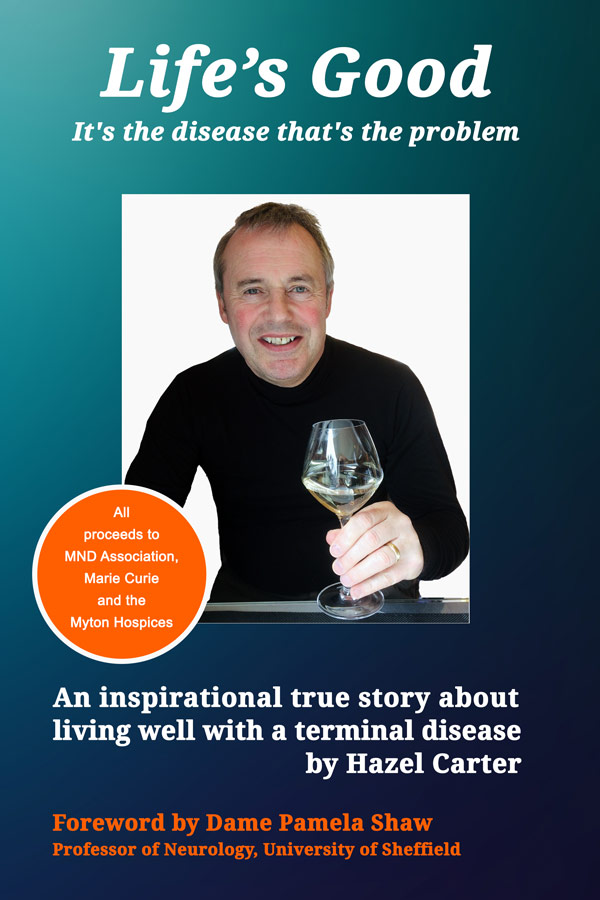

When my husband, Alan, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) in November 2017, our world turned upside down. Every aspect of our lives was changed dramatically. The future we planned together was destroyed, and we fell into a void of unpredictability with no hope of a positive outcome. There was also a massive ripple effect across our respective families, and our circle of friends.

Once the shock subsided, I became thirsty for knowledge, but due to the nature of the disease, there were no simple answers.

“MND affects everyone differently” was what I heard. It’s true, everyone’s physical journey with the condition is unique. However, anyone facing a terminal diagnosis has a massive mental battle on their hands.

In our case, sometimes, the psychological challenges turned out to be as great, if not greater, than the physical ones.

After hours of frantic research, I struggled to find detailed information, from the perspective of a family member carer. I wanted to know what to expect, or at least have some idea what the future might be like. I wanted tips on how to be an effective carer, and how to provide strong moral support to my dying husband.

This book aims to fill that void.

Can you imagine how you would feel if you or someone you loved, were told, within a year you will become completely paralysed, become dependent on a machine to help you breathe, lose your ability to speak and swallow, and maybe lose your mental capacity too?

When my husband, Alan, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) in November 2017, our world turned upside down. Every aspect of our lives was changed dramatically. The future we planned together was destroyed, and we fell into a void of unpredictability with no hope of a positive outcome. There was also a massive ripple effect across our respective families, and our circle of friends.

Once the shock subsided, I became thirsty for knowledge, but due to the nature of the disease, there were no simple answers.

“MND affects everyone differently” was what I heard. It’s true, everyone’s physical journey with the condition is unique. However, anyone facing a terminal diagnosis has a massive mental battle on their hands.

In our case, sometimes, the psychological challenges turned out to be as great, if not greater, than the physical ones.

After hours of frantic research, I struggled to find detailed information, from the perspective of a family member carer. I wanted to know what to expect, or at least have some idea what the future might be like. I wanted tips on how to be an effective carer, and how to provide strong moral support to my dying husband.

This book aims to fill that void.

Marie Curie Hospice, West Midlands

The Last Room

Within an hour of me reaching Warwick Hospital, where Alan had spent the last week, an ambulance crew arrived to move him to Marie Curie Hospice, Solihull.

A week ago, I thought Alan was going to die. For the second time in 2019 he had been rushed into hospital with a raging temperature, racing heart and low oxygen saturation levels. He had developed aspiration pneumonia because MND had weakened his swallowing muscles. As I followed the ambulance in my car, tears poured down my cheeks.

At the hospice, three nurses rallied around Alan and wheeled him into room number nine. Through the two wide, full-length windows to the left of the bed, I could see a lovely garden. I knew Alan would never walk in it, but I was told the bed could be wheeled outside on sunny days.

A heavy, high back, pale blue chair rested by the left side of the modern, high specification bed. The bed had buttons on its side so nurses could raise and lower Alan’s head and knees.

The whole bed could be lowered or raised so he could be washed or hoisted out into a chair. Opposite the bed was a recessed wash basin, with one of those special taps with a big paddle so it could be operated with your elbow or forearm. On the wall above the basin, there was a TV.

Next to the door into the room from the corridor, on the right of the bed, was a small grey, round table with two matching chairs. It sat under a window with venetian blinds to provide privacy from the corridor.

On the back wall, to the right of the bed, was a whiteboard. Attached to it was a bright green pot containing coloured marker pens. On the full-length maroon glass panel behind the headboard of the bed, were call buttons, gadgets, and lights – none of which Alan could access because, for many months, he had been completely paralysed.

From this day onwards, this clinical, but smart, twelve-foot by twelve-foot room would be the centre of our world, and the last room in which Alan would live.

Within an hour of me reaching Warwick Hospital, where Alan had spent the last week, an ambulance crew arrived to move him to Marie Curie Hospice, Solihull.

A week ago, I thought Alan was going to die. For the second time in 2019 he had been rushed into hospital with a raging temperature, racing heart and low oxygen saturation levels. He had developed aspiration pneumonia because MND had weakened his swallowing muscles. As I followed the ambulance in my car, tears poured down my cheeks.

At the hospice, three nurses rallied around Alan and wheeled him into room number nine. Through the two wide, full-length windows to the left of the bed, I could see a lovely garden. I knew Alan would never walk in it, but I was told the bed could be wheeled outside on sunny days.

A heavy, high back, pale blue chair rested by the left side of the modern, high specification bed. The bed had buttons on its side so nurses could raise and lower Alan’s head and knees.

The whole bed could be lowered or raised so he could be washed or hoisted out into a chair. Opposite the bed was a recessed wash basin, with one of those special taps with a big paddle so it could be operated with your elbow or forearm. On the wall above the basin, there was a TV.

Next to the door into the room from the corridor, on the right of the bed, was a small grey, round table with two matching chairs. It sat under a window with venetian blinds to provide privacy from the corridor.

On the back wall, to the right of the bed, was a whiteboard. Attached to it was a bright green pot containing coloured marker pens. On the full-length maroon glass panel behind the headboard of the bed, were call buttons, gadgets, and lights – none of which Alan could access because, for many months, he had been completely paralysed.

From this day onwards, this clinical, but smart, twelve-foot by twelve-foot room would be the centre of our world, and the last room in which Alan would live.